Cardiovascular Clues Derived From Pulsations in the Neck

Author:

Jacob J. Silverman, MD

Staten Island Hospital

Citation:

Silverman JJ. Cardiovascular clues derived from pulsations in the neck. Consultant. 1961;1:22-24.

Careful inspection of the neck veins and arteries takes only a few minutes, can be performed at the bedside, and provides a surprising number of diagnostic cardiovascular clues. It should be an integral part of every cardiac examination.

Congestive Heart Failure

In a recumbent patient whose head is raised to approximately 45° and rotated slightly, the cervical veins normally are empty and pulseless. In congestive heart failure, the jugular veins are distended and, depending on the degree of venous hypertension, a distinctive venous pulsation is observed. The key to venous pressure measurement at the bedside is the height of the “jugular meniscus,” that is, the highest level at which the rise and diastolic collapse of the jugular pulse is observed. The higher the level of the “jugular meniscus,” the greater the congestion and the higher the pressure. A tensely distended vein will not pulsate. External jugular veins that are both tortuous and engorged signify chronic venous hypertension of long standing.

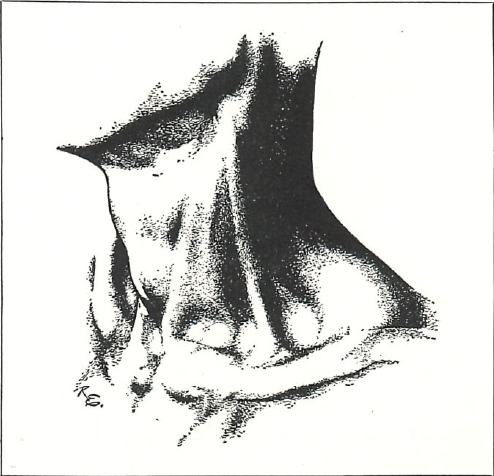

Venous pulsations in the neck must not be mistaken for arterial ones. Proper lighting as well as positioning of the patient is important to distinguish them. The light, preferably from a flashlight in a darkened room, should shine tangentially across, rather than directly at, the neck. (See illustration.) Venous pulsations are more diffuse, less easily palpable, and more sensitive to changes in posture, respiration, or abdominal pressure.

One of the earliest clinical clues to congestive heart failure is an abnormal hepatojugular reflux, characterized by intensification and maintenance of neck vein distention when pressure is applied over the liver or abdomen of a recumbent patient.

Incipient Heart Failure

Observation of the neck veins after a simple exercise test can be of real value in the diagnosis of incipient heart failure. In patients with limited cardiac reserve whose neck veins are ordinarily inconspicuous, slight exertion is apt to produce striking engorgement of the neck veins that persists for several minutes after the exercise has been stopped.

Arrhythmias

The diagnosis of atrial fibrillation based on flutter waves in the jugular pulse is difficult and unreliable. But gross irregularity of the carotid pulsations may be sufficiently apparent to establish the diagnosis.

The diagnosis of a “mid” or “low” AV nodal rhythm may be suspected by the regular appearance of extraordinarily large positive pulse waves in the neck veins. These large waves in the neck are known as “Cannon A” waves and are produced by contraction of the right auricle on a closed or closing tricuspid valve. “Cannon A” waves may also be observed with ventricular premature beats.

“Cannon A” waves are also helpful in differentiating between ventricular and supraventricular tachycardia. In ventricular tachycardia, irregular, independent “Cannon A” waves occur. They do not occur in supraventricular tachycardia, except in the unusual instance of AV dissociation with AV nodal tachycardia and retrograde block.

Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

One of the most striking features of superior vena cava syndrome is the intense engorgement of the veins of the neck and upper part of the body. The engorged cervical veins resulting from mediastinal obstruction are pulseless.

Aneurysm of the Aorta

Any unusual arterial pulsation in the lower neck should suggest the possibility of an aneurysm of the arch of the aorta. Heaving pulsations in the suprasternal notch and a systolic lifting of the manubrium may be observed. Marked inequality in the strength of the carotid pulsations is another clue that should suggest an aortic aneurysm. An enlarging aneurysm that obstructs the superior vena cava will cause bilateral, nonpulsating engorgement of the neck veins. Rupture of an aneurysm into the right side of the circulation will convert venous pulsations of the neck to arterial.

Dissecting Aneurysm of the Aorta

Vigorous pulsation in either the right or left sternoclavicular joint suggests a diagnosis of dissecting aneurysm of the aorta rather than myocardial infarction. So does an inequality of the carotid pulsations. Rarely, superior vena cava syndrome with marked distention of the neck veins is a manifestation of aortic dissection.

Aortic Insufficiency

In free aortic insufficiency, or regurgitation, the arterial pulsation is characterized by a quick, sharp rise, and an abrupt collapse. This jerky pulsation in the suprasternal notch and along the lateral side of the neck may be pronounced enough to suggest the diagnosis at a glance.

The rhythmic backward movement of the head and neck with each systole, occasionally observed in aortic insufficiency, is known as the sign of DeMusset.

Aortic Stenosis

A small, lazy pulsation at the carotids, in contrast to a powerful impulse at the apex, is a feature of advanced aortic stenosis. A palpable, doublepeaked carotid pulse followed by an abrupt collapse (which is sometimes mistaken for coupling) is a reliable sign that significant regurgitation is also present.

The Kinked Innominate Vein or Kinked Carotid Artery

In contrast to the bilateral venous hypertension of heart failure, unilateral engorgement of the left jugular vein suggests a high and probably rigid aorta that is compressing the left innominate vein from below. Interestingly, a pulsating mass at the base of the neck, right or left, and sometimes in the suprasternal notch, may be caused by a high aortic arch secondary to hypertension and arteriosclerosis. While the kinked innominate vein occurs equally as often in men as in women, the kinked carotid occurs almost exclusively in women.

Tricuspid Insufficiency or Stenosis

Extraordinary pulsations in the neck veins occur in the patient with advanced tricuspid insufficiency. His veins are characteristically engorged, and during systole, a powerful, positive jugular pulsation is observed. This powerful venous systolic thrust actually may lift the sternocleidomastoid muscle and is often mistaken for a carotid pulsation. A precipitous collapse of the jugular pulse coincident with diastolic expansion of the chest is a feature of advanced tricuspid insufficiency.

In contrast to the powerful systolic pulsation that occurs in tricuspid insufficiency, tricuspid stenosis is characterized by a positive presystolic wave in the jugular pulse. This presystolic pulsation does not change with change of posture and is present only when cardiac rhythm is regular. A diastolic collapsing type of jugular pulse is never observed. Placing the patient with tricuspid stenosis in a recumbent position will cause intense congestion and cyanosis of the face, and distention of the veins of the neck and head.

A thorough and careful physical examination of the cardiac patient may yield enough diagnostic clues to limit the need for more sophisticated, time-consuming, and expensive tests.

Jacob J. Silverman, MD, is attending physician and Chief of the Cardiac Clinic at the Staten Island Hospital, Staten Island, New York. He is also cardiac consultant at the U. S. P. H. S. Hospital and St. Vincent's Hospital, Staten Island. Dr. Silverman received his medical education at Tufts University School of Medicine. He is a Fellow of the American College of Physicians. He has published approximately 50 medical articles and wrote one of the sections in CARDIOLOGY: AN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM (Blakiston).