A Rare Cause of Neck Pain and Headache

An 8-year-old boy presented with a history of 3 weeks of progressively worsening headache and neck pain, prior to transfer to our institution. Other than the 3 previous weeks of pain, he reported no prior history of headaches or neck pain. His parents had initially felt he was just “sleeping wrong,” but a local emergency department (ED) evaluation had raised concerns of meningitis on day 4 of the boy’s illness, The boy underwent a lumbar puncture in the ED, with normal results. He was diagnosed as having muscle spasms, and diazepam was prescribed.

However, the boy’s symptoms persisted after discharge from the ED, and his pediatrician at follow up had diagnosed streptococcal pharyngitis and prescribed a 10-day course of amoxicillin. At this time, the boy had no nausea, vomiting, or focal neurologic signs, and his pain was localized to the back of the neck at the base of the skull. He reported having subjective low-grade fevers that he had treated with acetaminophen and ibuprofen and that were somewhat relieved by warm showers. However, due to persistent headaches and neck pain, the boy was directly admitted to his local hospital after visiting his pediatrician for a third follow-up visit. At that time he underwent a computed tomography scan of the head, and results showed a low-density area to the posterior aspect of the nasopharynx measuring 1.9 cm × 2.9 cm. He was then transferred to our institution, where laboratory tests and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were ordered.

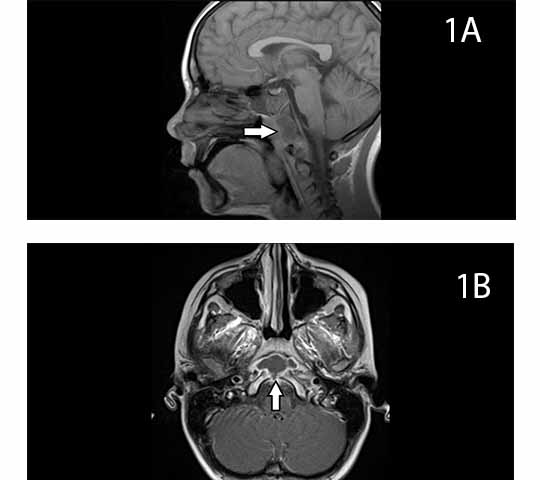

The results of laboratory tests revealed C-reactive protein of 94.6 mg/L (reference range, 0 to 4.9 mg/L), erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 63 mm/h (reference range, 0 to < 20 mm/hr), and white blood cell count of 12,000 cells/mm3 (reference range, 4500 to 13,000 cells/mm3) without left shift. Nasopharyngeal MRI (Figures 1A-1B) revealed skull base osteomyelitis with a relatively discrete abscess cavity formed in the clivus without any other anatomic abnormalities. No other sources of infection were appreciated.

Figures 1A and 1B. Pretreatment, sagittal view and axial view.

The otolaryngology and neurosurgery departments were consulted, and antibiotics were delayed pending surgery for biopsy since the patient was stable without fever, had appropriate mentation, and had no focal neurologic signs.

Forty-eight hours after admission, a pediatric otolaryngologist was able to perform a functional endoscopic sinus surgery with aspiration of purulent material, with possible cause of infection from the sphenoid sinus. Cultures were obtained, the patient was started on ceftriaxone and clindamycin, and the aspirate grew microaerophilic Streptococcus species. As per protocol at our institution, no sensitivities were provided.

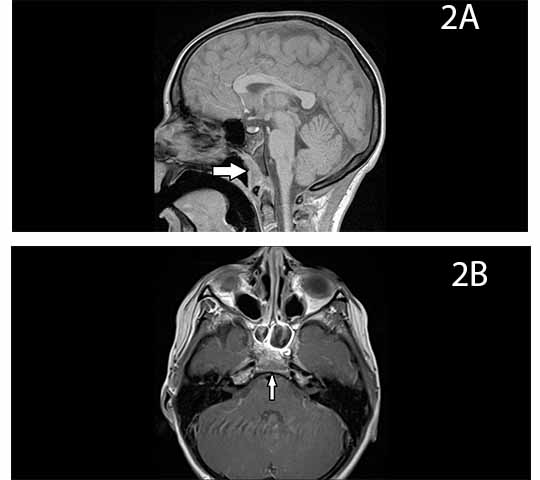

The boy was discharged on hospital day 11 with a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line, and he completed a total of 4 weeks of intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone and clindamycin before transitioning to oral cefdinir and clindamycin to complete a total of 6-8 weeks of antibiotics. . After 2 weeks of oral antibiotics, his inflammatory markers were within normal range and antibiotics were discontinued. An MRI with and without contrast was conducted 4 months posttreatment and revealed resolution of the abscess and new bone formation of the clivus (Figures 2A-2B).

Figures 2A and 2B. Posttreatment, sagittal view and axial view.

Discussion

The clivus (Latin for “hill”) is a sloping structure located between the foramen magnum and the dorsum sellae.1 Clivus abnormalities represent a spectrum of pathology that includes neoplasms, vascular abnormalities, granulomatous disease, and infection.2,3 Osteomyelitis with abscess of the clivus is a rare condition in the adult population, and it is even more rare in children. Infection of the clivus most commonly arises by direct spread from the sphenoid sinus from a chronic infection that has been inadequately treated.4 A hematogenous route of infection is also possible.1,5 Given the diverse causes of infection, prior case studies and research have revealed a variety of causative organisms, including Staphylococcus species, Pseudomonas species, Enterococcus faecalis, Gemella haemolysans, various Streptococcal species, Fusobacterium necrophorum, anaerobes, and even culture-negative infections.1-12

Diagnosis of clivus infection may be delayed because it is a rare cause of headache and neck pain. This tendency to delay diagnosis was apparent in the case of our patient, who was initially diagnosed with muscle spasms. Once the correct diagnosis is made, treatment often requires prolonged IV antibiotics with transition to oral administration, although no set guidelines have been established.

Surgical access is difficult and requires the skill of an otolaryngologist or neurosurgeon. If possible, broad-spectrum antibiotics should not be initiated until samples for culture have been obtained, and antibiotics should be adjusted based on culture and sensitivity results. Our patient is currently well and has no sequelae posttreatment, which is consistent with outcomes of other reported cases of clivus infection.

General pediatricians should be aware of the possibility of clivus infection, even though it is rare. Children may present with headache or neck pain as the only symptom11 of this potentially serious medical condition, and delay in treatment can result in subsequent morbidity.

James F. Buscher, MD, is a pediatric resident at the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida.

Ravi S. Samraj, MD, and Bahareh E. Keith, DO, MHSc, are assistant professors at the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida.

Judy F. Lew, MD; Michele N. Lossius, MD; William O. Collins, MD; and Kathleen Ryan, MD, are associate professors at the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida.

References

1. Azizi SA, Fayad PB, Fulbright R, Giroux ML, Waxman SG. Clivus and cervical spinal osteomyelitis with epidural abscess presenting with multiple cranial neuropathies. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1995;97(3):239-244. doi: dx.doi.org/10.1016/0303-8467(95)00036-J.

2. Prabhu SP, Zinkus T, Cheng AG, Rahbar R. Clival osteomyelitis resulting from spread of infection through the fossa navicularis magna in a child. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39(9):995-998. doi:10.1007/s00247-009-1283-9.

3. Rusconi R, Bergamaschi S, Cazzavillan A, Carnelli V. Clivus osteomyelitis secondary to Enterococcus faecium infection in a 6-year-old girl. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69(9):1265-1268. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.03.015.

4. Pincus D, Armstrong M, Thaller S. Osteomyelitis of the craniofacial skeleton. Semin Plast Surg. 2009; 23(2):73-79. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1214159.

5. Nabavizadeh SA, Vossough A, Pollock AN. Clival osteomyelitis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(9):1030-1032. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182a37755.

6. Bates DD, Shetty AK, Kirse DJ. Treatment of a clivus abscess in a child using image-guidance. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol Extra. 2006;1(3):207-212. doi: dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pedex.2006.03.007.

7. Chua R, Shapiro S. A mucopyocele of the clivus: case report. Neurosurgery. 1996;39(3):589-90; discussion 590-591. doi:10.1097/00006123-199609000-00031.

8. Clark M, Pretorius P, Byren I, Milford C. Central or atypical skull base osteomyelitis: diagnosis and treatment. Skull Base. 2009;19(4):247-254. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1115325.

9. Hayashi T, Uchiumi H, Yanagisawa K, et al. Recurrent Gemella haemolysans meningitis in a patient with osteomyelitis of the clivus. Intern Med. 2013;52(18):2145-2147. doi: doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.52.0436.

10. He J, Lam JCL, Adlan T. Clival osteomyelitis and hypoglossal nerve palsy—rare complications of Lemierre's syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015. pii: bcr2015209777. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-209777.

11. Laurens MB, Becker RM, Johnson JK, Wolf JS, Kotloff KL. MRSA with progression from otitis media and sphenoid sinusitis to clival osteomyelitis, pachymeningitis and abducens nerve palsy in an immunocompetent 10-year-old patient. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72(7):945-951. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.02.025.

12. Singh A, Khabori M, Hyder M. Skull base osteomyelitis: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in atypical presentation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133(1):121-125. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2005.03.024.